"How can you just leave for work like that when your husband is so sick? So, your work is more important than your husband, is it?

I don’t know about your family, but we are not so poor that we need you to bring in money.

Once a woman gets married, it’s her duty to serve her husband..."

Synopsis:

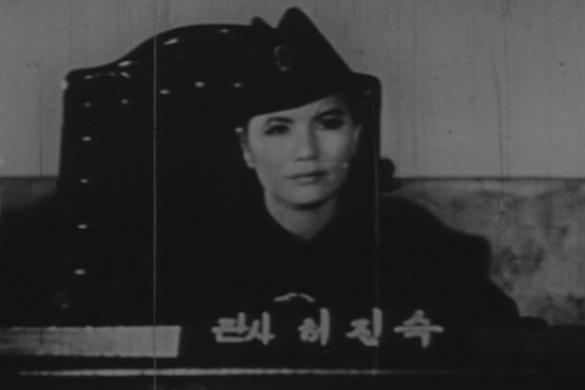

Despite her mother's repeated protestations that she should find a man, get married and settle down to a life as a housewife, Jin-suk continues to study virtually night and day for an exam which would qualify her as a judge. Not long after passing the exam and beginning her new career, Jin-suk catches the eye of construction company boss Mr Kwon who, both impressed with her fairly lofty professional position and quite taken with her effervescent beauty, soon becomes obsessed with seeing her married to his son, Gyu-sik. When Jin-suk’s current would-be relationship disintegrates as a result of the man in question demanding that she give up her dream of a professional career (something she would not for a single second consider), she finally begins to date Gyu-sik and the two are indeed eventually wed.

However, as Jin-suk tries to find a balance between her new home responsibilities and her all-important work, jealousies from both her (new) immediate and extended family start to emerge; jealousies that could ultimately put her very life in mortal danger...

Review:

Thematically and indeed in terms of narrative focus, A Woman Judge can almost be considered as consisting of two parts; one morphing into the other at pretty much the film's halfway point.

The first of these is wholly centred on Jin-suk’s rather insecure position within her husband's family as she tries to balance judicial responsibilities and familial demands; others' (vastly differing and often negative) attitudes to her fairly lofty professional position; and the repeated efforts of some to wholly derail both her work aspirations and her attempts to fit in as best she can with the traditional notion of a woman's requirement of providing for the needs of her husband first and foremost and, to almost as great an extent, the demands of her mother-in-law (or more accurately her step-mother-in-law).

From the very outset of A Woman Judge, director Hong Eun-won deftly compares the virtual polar opposite attitudes towards Jin-suk from those around her – male vs. female; young vs. old – and it is here that A Woman Judge both shows it's strength and brings some surprises:

The wholly supporting attitudes of males of middle age (namely Jin-suk’s father and father-in-law) towards her professional efforts stand in stark contrast to those of her mother and step-mother-in-law who both feel she should abandon her career and take her place servicing the needs of her husband, as they feel should be the case for all women of the time. While this in itself is thematically insightful, what is all the more engagingly surprising is the fact that the younger people around her – her husband, her sister-in-law; her ex-boyfriend etc.) have attitudes as equally as traditionally conservative and close-minded as the middle-aged matriarchal family members. However, what stands out most of all is the fact that almost every woman Jin-suk comes into contact with stands in opposition to her life choices, and even those females outwardly showing support are largely only doing so to cover their backstabbing or because they think they can somehow benefit from Jin-suk's professional power, rather than truly believing that a woman has a rightful place in professional society. In fact, even when Jin-suk’s husband is found to be cheating on her with a female work colleague, the general attitude of gossiping female family and associates is that Jin-suk must simply have driven him to it by failing in her marital duties to him because of her (unnecessary) job. Whether this wholly disparaging standpoint is a result of the traditional ideals drummed into women of the time from early youth to adulthood; jealously stemming from Jin-suk succeeding where they simply couldn't; or a combination of the two is never definitely stated but the question does beautifully give pause for thought and further allows A Woman Judge to linger in the mind long after the credits role.

This first part/half of A Woman Judge also has some understatedly humorous moments that while lightening the load somewhat still speak of societal issues, historically. For example, we see Jin-suk adjudicate a law case of male against female in which the woman in question states that she only slept with the man because she thought they would be eventually married, to which Jin-suk asks “So, did you also assume you were going to marry all the other men you've slept with before this?”, an outburst of raucous laughter and even sniggers from the court audience immediately following. However, serious really is the name of the game overall here as A Woman Judge moves into its second thematic and narrative section:

This second part/half of A Woman Judge is heralded by the death of a supporting character – perhaps as a result of foul play; perhaps with Jin-suk being the true intended target. The majority of the subsequent narrative focuses on efforts to unveil the supposed perpetrator and the trial to bring them to justice and though this section’s ultimate outcome is eventually shown to indeed relate to the themes of the first ‘part’ (underlining how events allow Jin-suk to finally cement her position in the family as a wife with a worthy career and her place within society as a forward-thinking, modern woman) the change in tone from insightful, societal drama to murder/mystery thriller does, for a time at least, make A Woman Judge feel somewhat like two separate films spliced together. That's not a huge criticism particularly but it is noticeable nonetheless to the extent that that switch in focus, style, genre and depiction rather remains in the mind even as the overarching, linking themes are finally revealed and leaving a feeling of jarring digression to a degree.

|

As was sadly the case for a great many Korean films of the Golden Age and earlier, A Woman Judge was for decades lost with no prints believed to have survived. However, in 2015 a rather well used and fairly worn 16mm print surfaced which the Korean Film Archive acquired, subsequently restored (as much as was possible with such a damaged print), digitized and made available on the KOFA YouTube channel:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vXfHTj754oU

Of course , a 16mm print has a much smaller original frame size than a 35mm or 70mm frame and as such the image is noticeably ‘softer’ and far from pin-sharp. There are also numerous scratches (some small and passing, others more severe and continuing) throughout the film. Not only that, but a couple of scenes had portions so damaged the offending moments had to be removed and the two ends spliced together (if you will) but the Korean Film Archive has done an absolutely superlative job of making sure viewers can easily understand the entire narrative in spite of this. For example, one scene ends rather abruptly with a character still needing to speak a final line of dialogue, but even though that dialogue line’s audio and visuals are missing KOFA provides the relevant subtitles anyway, so audiences are fully aware of what was originally said. Aurally, things hold together fairly well with issues being little more than a few crackles and noise, but nothing that prevents anything from being heard.

All in all, though this 16mm print was in pretty bad shape, none of the above issues interfered with my immersion in the narrative and though KOFA even includes a disclaimer on its YouTube channel about the severe damage the print suffered over the years, viewers should ultimately be wholly grateful for the work the Archive has undertaken to make A Woman Judge available to Korean film fans in as good a state as was possible, making sure the narrative is entirely understandable in spite of any scene parts missing in the process.

|

Director Hong Eun-won first became involved in the Korean film industry after becoming a member of the Shin Kyung Music Choirs in Manchuria and there meeting director Choi Yin-gyu. Working as a continuity girl for director Choi for over a decade, she progressed to the roles of script supervisor and eventually assistant director for a number of films through the late 50s and early 60s. A Woman Judge was her first feature as director – made when she was 40 years old – and in fact the film was at its time of release only the second Korean film ever helmed by a female; the first being Park Nam-ok’s 1955 highly respected drama A Widow. Throughout her career, Hong Eun-won repeatedly stated that her primary desire was to make and tell stories of the lives and struggles faced by (at that time, contemporary) women in Korea from a female perspective within an almost wholly male-dominated industry. In terms of such, A Woman Judge can truly be considered as the accomplishment of that goal, certainly if we especially focus on the somewhat more thematically in-depth first half, and its narrative overall stands as far more worthy than the veritable slew of male-directed melodramatic tearjerkers that were streaming out of Korea at the time. In fact, A Woman Judge sits far more closely to films now deemed to be classic examples of Golden Age Korean cinema helmed by masterful directors such as Kim Ki-young and the like and for a female director's feature debut that really is saying something.

Considering the number of current female Korean directors I’ve personally spoken to about film-making challenges – each and every one of whom has talked at length about the huge difficulties faced by women in the still male-dominated Korean film industry, both in terms of getting productions green-lighted and funded and indeed subsequently released – I can only imagine how near impossible it was for directors like Hong Eun-won and Park Nam-ok working as women in a far less enlightened age. As such, huge credit should be given to Hong Eun-won for succeeding in directing a further two films after A Woman Judge – A Single Mom (1964) and What Misunderstanding Left Behind (1966). However, though each were as thematically worthy as her debut film, audiences and indeed critics at the time gave her work little attention and it wasn’t until many years later that accolades for her films started to appear. That in itself combined with the aforementioned difficulties faced by women working in and on Korean films during the Golden Age likely played a part in nudging her towards screenwriting and away from directing in the very late 60s and may well have been a factor in her departure from the industry entirely after 1970, whether by deliberate design or circumstance. That, to my mind, is a pity to the nth degree and a huge loss to both classic Korean films as a whole and to the Korean film industry’s history which she frankly should have been a far bigger part of.

|

Summary:

Though Hong Eun-won’s A Woman Judge does for a time feel somewhat like two separate films spliced together, it nonetheless stands far closer to classic Golden Age films helmed by masterful directors such as Kim Ki-young and the like than to the plethora of fairly throwaway male-helmed melodramas that rather pervaded Korean cinema output at the time; made all the more important by the fact that it was only the second ever Korean film to be directed by a female.

여판사 A Woman Judge (1962)

Director: Hong Eun-won

Starring: Moon Jung-suk

|